The Need for More Stringent Marine Fisheries Policy

By Michael Coleman

As the fisheries industry expanded throughout the early and mid-1900s, many fishing operations functioned under the assumption that aquatic resources were essentially unlimited. It was believed that the vast populations of aquatic life couldn’t be affected by human action, and fisheries were left unchecked. However, as fisheries perpetually overharvested for years on end and technology increased to allow greater monitoring and targeting of fish stocks, the general consensus has shifted. Now, fisheries and the bodies that govern them are well aware of the common occurrence of fish stock depletion and degradation and have sought to pass regulation to prevent this occurrence. However, marine fisheries policy in the U.S. is still far behind global guidelines and must be expanded accordingly.

To provide some broader context, we can turn to a set of guidelines called the Sustainable Development Goals. Passed in 2012 at the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, this set of goals outlined tangible and relevant objectives for countries to work towards for the betterment of social, economic, and environmental health.[1] More specifically, SDG #14 directly addresses the prospect of sustainable marine health from a resource management perspective. The goal of SDG #14 is to “conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development”[2]. This goal goes to great lengths in prioritizing sustainability as a policy benchmark. This goal does not propose to manage marine resources in a way that entirely restricts resource extraction, but rather advocates for a system of use that simultaneously allows for resource use and marine health.

Despite the passing of these goals and subsequent legislation in various parts of the world to begin working towards SDG #14, studies show that wild fishery populations continue to be in decline. In fact, the WWF estimates that “two-thirds of the world's fish stocks are either fished at their limit or overfished”[3]. Although a myriad of conditions contributes to overall marine health, the effect of the fishing industry is in no way minimal. And despite global concerns and guidelines aimed at strengthening the health of these fish stocks, conclusive progress has not yet been made.

Addressing this problem on a global scale would be a monumental task requiring commitments and cooperation from hundreds of countries with unique circumstances and challenges. By narrowing this issue to only the United States, it allows Congress to more feasibly consider possible strategies and implementation plans to better align with SDG #14 in our country.

To better align with SDG #14 and conserve fish stocks, I propose the expansion of the Magnuson-Stevens Act under the guidance of Congress. The Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA) was first established in 1976, but was amended multiple times as recently as 2006. In short, the MSA was passed in order to establish limitations on the total quantity of fish that was allowed to be harvested by US fisheries on an annual basis. The MSA provided for data collection of commercial fish stocks that were commonly fished for in the US, and from this data established guiding values such as the Annual Catch Limit, Acceptable Biological Catch, and Overfishing Limit.[4] This Act was the first of its kind in attempting to limit the total yield that fisheries are able to extract under a certain time period. However, this Act also has shortcomings that limited its full effectiveness.

One of the most glaring limitations is that this Act fails to include punishments for fisheries that break the specified limits. Secondly, the Act did not allocate additional resources for the surveying and monitoring of major fisheries in the US to ensure guidelines were being followed. As a result, some critics argue that the MSA did not effectively prevent overfishing. To correct this, it is my proposal that the MSA be amended once again to include both a system of repercussions, as well as provisions for monitoring accountability of major fisheries. On the first point, a possible punishment system could include a penalty system in which fisheries found to be in violation of the MSA receive strikes, and a certain amount of strikes results in a revoking of the fishery’s operational license for a short period of time. Repeat offenders would face increasingly long suspension periods if they continue to violate the MSA.

Second among my suggestions is the creation of a new bill allocating increased government funding to the growing aquaculture industry. Aquaculture typically refers to the raising and harvesting of fish stocks in contained environments, for the purpose of sale. The OECD estimates the aquaculture industry has been growing at a rate of 2.1% per year since 2011, and that much of this growth has been in response to cover inadequacies with wild fish stock yields.[5] I believe that this industry can help alleviate some of the pressure placed upon wild fish stocks and allow them a better chance to recover to more sustainable levels. Because of this, I believe it is necessary for Congress to help foster growth in this industry and provide financial support in the form of tax breaks and subsidies for aquaculture operations within the country.

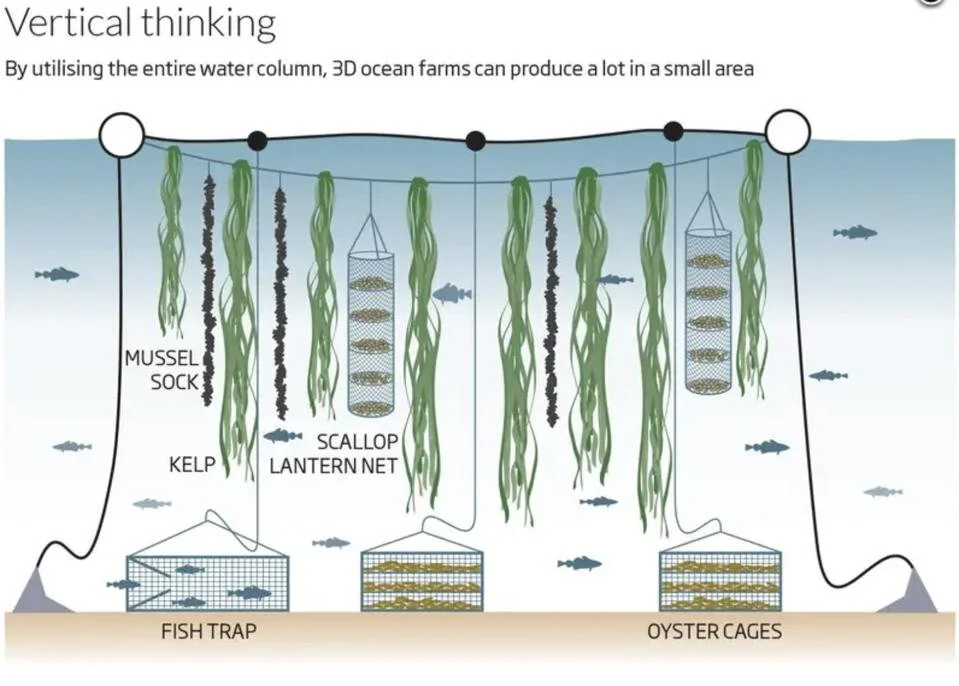

Lastly, in the interest of ensuring fish stocks remain at healthy, maintainable levels, regenerative ocean farming can provide a model that actually goes beyond sustainability and hopefully gives us a taste for what the future of the fisheries industry may look like. Put simply, regenerative ocean farming is a means of producing seafood in a way that cleans the water, sequesters carbon, increases biodiversity, and produces food, fuel, fiber, and medicine for human uses with zero freshwater inputs, zero pesticide inputs, and zero fertilizer inputs. In short, regenerative aquaculture neutralizes many of the biggest drawbacks of other aquaculture operations and while producing net ecological benefits in addition to the fish stock being harvested. What's more, the farming process can be done in a much lower energy way than land-based farming due in part to the ease of travel on flat/low-friction water, and the fact that the production systems take place in 3D space as opposed to using the more or less 2 dimensional plane of the soil for land based farming.

Copyright Greenwave.org

It is a potentially revolutionary offshoot of traditional aquaculture that prioritizes ecosystem health and spatial management in the seafood growing and harvesting process. Despite the benefits of aquaculture, these are often areas that traditional aquaculture operations fail to accommodate, and aquaculture also has issues of pollution, animal welfare, fish feed sourcing issues, and nutritional quality to deal with. To highlight one such example of this system operating successfully, we can look towards regenerative ocean farming non-profit GreenWave. By highly optimizing vertical space and farming multiple species simultaneously, the GreenWave farm model produces high yields using reduced space.[6] It is worth noting that most regenerative ocean farming companies are focused on non-fish seafood such as kelp, mussels, scallops, clams etc. However, Bren Smith’s for-profit entity Thimble Island Ocean farm has apparently become one of the most popular spots for recreational and small scale commercial fishers since the habitat and ecology he has created draws in many fish from the area. Besides the obvious economic incentive of producing high yields using little ocean space, startup costs for fishers looking to adopt this model are much lower than launching a large aquaculture operation, or a land based farm. Boasting both economic and ecological boons for farmers and the environment, regenerative ocean farming presents itself as a key component in the future of the fisheries industry.

Ultimately, marine health remains a multi-faceted global problem that will likely require more time and effort to fully reach the goals outlined by SDG #14. However, I believe expanding existing marine fisheries policy like the Magnuson-Stevens Act and introducing new policy to stimulate a more regenerative aquaculture industry would embark the US on the right path to meeting this goal on our own national scale.

[1] “Background of the Sustainable Development Goals,” UNDP, accessed March 5, 2020, https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/background.html)

[2] United Nations, “Goal 14 .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform,” (United Nations), accessed March 5, 2020, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg14)

[3] “Decreasing Fish Stocks,” WWF, accessed March 5, 2020, https://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/endangered_species/cetaceans/threats/fishstocks/)

[4] American Fisheries Society, February 28, 2020, https://fisheries.org/policy-media/magnuson-stevens-act/)

[5] Stephen Castle, “As Wild Salmon Decline, Norway Pressures Its Giant Fish Farms,” The New York Times (The New York Times, November 6, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/06/world/europe/salmon-norway-fish-farms.html)

[6] “Our Model.” GreenWave, www.greenwave.org/our-model.